How do horns grow in cattle?

Case study: Cattle horn development.

In dairy and beef production, there is a pressure towards breeding for hornless - or polled - cattle because there are concerns for the welfare of horned animals.

Producers routinely disbud horned calves to stop horns from growing because they are a danger to the animals and their handlers. While this procedure does improve the safety of herd-mates and handlers, it impacts the welfare of the animals.

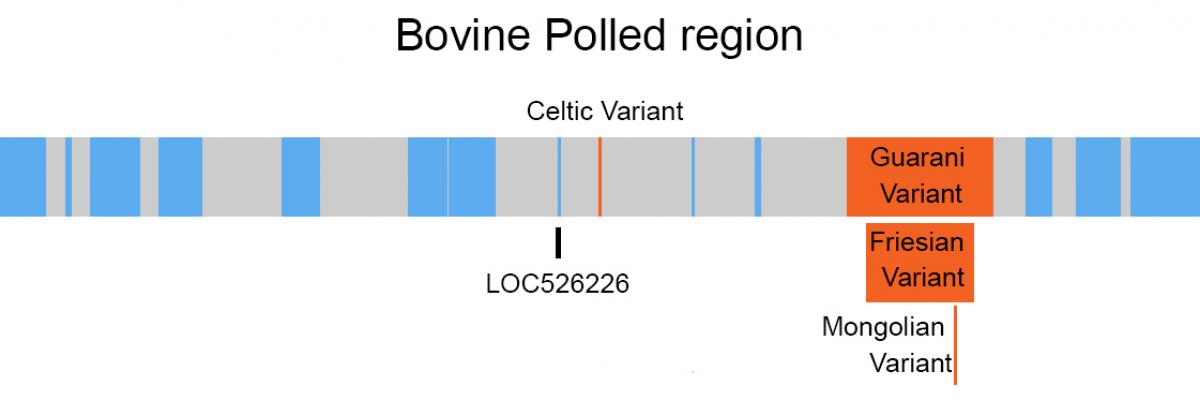

Hornless - or polled - cattle are also naturally occurring. Polledness in cattle is associated with four genetic variants that all occur in the same region of chromosome 1.

Johanna Aldersey, a PhD candidate at the University of Adelaide, is studying the molecular pathway(s) that cause horns to grow in cattle.

“The variants are not located within any genes, so we don’t know which pathways are being affected,” said Johanna.

“We think the variants change the expression of nearby genes.” Although the gene order of this region is well conserved across horned and hornless species, one gene in this region, LOC526226, is unique to cattle. (Figure 1)

Fig 1. Location of polled gene LOC526226 in cattle

An RNA sequencing experiment was conducted to investigate this hypothesis, in which gene expression in the horn bud growing regions is being compared between horned and polled bovine foetuses. Early studies reported that the horn bud was visible at 60 days of development.

“We wanted to study gene expression just before the horn bud formation, so we chose to study 58 day old foetuses for our experiment. We found that the horn bud is already formed at 58 days, and the horn bud appears as a ring of depressed skin,” said Johanna.

“This is not seen on the 58-day old polled foetuses that have smooth skin at this site.”

Histological analysis of the horned foetuses showed that the epidermis of the horn bud is six to eight layers thick, whereas the surrounding tissue only has one or two layers. There also appears to be an aggregation of cells within the dermis that is not seen in polled foetuses.

“Given these differences, comparing the gene expression of horned and polled foetuses will be useful in uncovering the genes and pathways that are important for the formation of the horn bud,” said Johanna. The RNAseq data is currently being analysed.

Johanna is excited for the RNAseq results.

“This is the earliest gestational age that gene expression has been studied to understand horn development in cattle.”

This study will contribute to the understanding of how horns develop and how the genetic variants affect normal development.

Horns are a unique characteristic of Bovidae, and this research in cattle could potentially translate to other important related domestic species such as sheep and goats.