Fee Setting for Veterinary Services

Clients usually ask about cost before purchasing a service or product because getting a quality service for a fair price is important to most people.

For the veterinarian it is important to have an understanding of how fees are derived as this will give you confidence that the client is being charged an appropriate fee for service.

Watch our short films

From a young vet: pricing of veterinary services

Understanding 'loss-leaders' - a discussion of low de-sexing prices

Download a pdf of the learning guide shown below.

-

Introduction to fee setting

Health care for animals involves professional service provision by a veterinarian and may also include the provision of drugs and other animal health items. Veterinary businesses have a fee schedule (price list) for staff to use to inform clients of prices for professional services. The full fee schedule for services, drugs and other animal health items is generally held on a computer based debtor program. A hard copy of common professional fees usually held at the reception desk. Both of these documents are known as a fee schedule.

It is advantageous for veterinarians to have a working knowledge of methods for arriving at pricing of services and animal health items. These topic notes do not intend to teach deeply into accounting methods, rather the notes provide an introduction to concepts behind pricing, via the cost-plus method of pricing for services.

A further set of topic notes, Pricing Animal Health Items, introduces the mark-up method for pricing of items, such as drugs and external pathology.

For a detailed discussion on factors that influence pricing decisions, and alternative approaches to pricing, refer to Chapter 8 in the text Cost Accounting: a Managerial Emphasis by Horngren et al. (2011).

Why does it cost that much, doc?

Some clients perceive that veterinary fees are expensive and you may be asked why this is the case. In this situation it is useful to discuss the expense of medical and dental fees, before the medicare or private health insurance rebate is applied.

It is also worth discussing with the client how much medicare levy they pay each year.

Explaining that the human health care system does not underpin the animal health care system may help a client understand the expense of veterinary services and the merits of pet insurance.

Cost-plus pricing and the effects of discounting

It has been suggested that if veterinary businesses employed cost-plus pricing, which is a fair and equitable pricing method, then competition by discounting would decrease. This would result in less confusion for clients as variability in fees between practices and services would be reduced. An example of lack of consistency in pricing is that of heavily discounted de-sexing. Discounting has a number of flow-on effects including:

- the need for compensatory inflation of the cost of other services, such as dentistry

- inadvertent depression of estimates for other simple procedures, such as laparotomies, and

- depression of practice profitability, which suppresses wage and salary increases.

Many veterinarians base their fees on what other veterinary practices charge, either by reference to a fee survey or by having a staff member phone neighbouring practices, and this pricing method has contributed to the low profitability of veterinary businesses. This topic requires that you consider the deficiency of this method of fee setting.

Reading and understanding the concepts presented in this topic, and the related topic Pricing Animal Health Items, will contribute to your understanding of costs involved in veterinary business and the inherent dangers of basing prices on the practices around you and discounting, whether hidden, accidental or purposeful.

-

Veterinary professional service fees

As indicated above, veterinary fees cover the provision of professional services and related animal health items. Veterinary items include drugs, pathology and non-prescription (over the counter) animal health items. Veterinary professional services are services that a business provides to a client. Examples of professional services include:

- consultations

- anaesthesia

- surgery

- support staff services

- hospitalisation

- in-house, internally provided, pathology procedural fees, e.g. microscopy, haematocrit

- diagnostic imaging, such as radiology and ultrasound

- dispensing and injection fees

- travel to animal(s) location

-

Pricing of veterinary service fees using the cost-plus method

Fee setting for veterinary surgery is complex so use a process that is fair and justifiable, such as the cost-plus method.

Provision of veterinary professional services is the core business of the typical veterinary practice. To provide quality professional services, the business must invest in, and maintain, two very important areas: technically fitted out facilities and trained core staff. As both areas involve significant costs to a veterinary business, income from veterinary professional services needs to cover the associated overhead costs.

To arrive at fair and justifiable fees, it is important for the practice management team to use an appropriate process of calculation. A cost based approach, also known as the cost-plus pricing method, begins with the question: 'Given what it costs to supply this service, what price should be set to recoup costs and achieve a return on investment?' (Horngren et al. 2011).

Cost-plus pricing for services is based on overhead costs and the addition of a required margin, as shown in the following formula:

Overhead + Margin Required = Price (Fee)

Overhead is the total fixed costs for the business, for example rent, electricity, rates, wages, insurances and administrative costs. These types of costs enable the business to operate and cannot quickly be altered or changed, hence they are known as overhead or fixed costs.

The margin is the difference between the total costs (expenses) to the practice of delivering a service or product, and the final price to the client.

The margin required needs to be sufficient to allow for contingency, asset and staff development, capital pay-down of loans, increases in compensation for staff members and the owners for the actual business. Although the margin is often called the profit margin, the author advises against considering the margin to be profit, as at the end of the financial year, some of the components of the margin will have been spent on expenses, such as staff training or increased wages. A tax accountant determines actual profit and this is inevitably less than the margin. As a business enters a plateau phase, when asset purchase or staff development is steady, actual profit will be closer to the targeted margin. However, veterinary businesses are often in growth phases, for example allocating finances towards building a new facility, or purchasing new technology. Therefore, it is worthwhile that, for an annual fee schedule review, the required margin over forecasted overheads is calculated to determine if a fee increase is required and to what extent, rather than applying a blanket fee increase of x% each year.

A lack of understanding of the cost to provide a service or product may result in unprofitable service provision, or losses. Also, good costing and pricing methods allow the business to determine which products or services yield the greatest margin, and this helps strategic planning. If you are interested in further information, you may wish to explore more on pricing strategies and the Boston Matrix.

-

Deriving a per minute rate for setting professional fees

The core business of a veterinary practice is the sale of services, and the key inputs to the provision of veterinary services are human input, that is knowledge and time. Hence, the process for deriving the price for a veterinary service is a time based costing method that accounts for time spent by the veterinarian and/or support staff. A per minute rate is calculated by determining annual overhead, the margin required to cover additional expenses, target annual professional services income and considering the realistic billable time. Steps one to five, below, outline calculation of per minute rate in detail.

- Determine annual overhead: Total annual overhead is the total of all fixed costs for a twelve month period. Fixed costs are costs that are essential to the business such as rent, wages and electricity. The total annual overhead does not include variable cost items which are items that are typically ordered when needed, and do not necessarily need to be purchased to keep the business operational, such as stock and external services. The business' most recent twelve month Profit and Loss Financial Statement contains cost and expense lines, which can be divided into variable costs and fixed costs (overhead), see Table 1.

Table 1: A simplified income statement (profit and loss) for a veterinary practice Total sales $1,404,652 Less: Variable Costs (items) $406,500 $406,500 Less: Expenses

(fixed costs or overhead)$631,496 $934,174

(total overhead)$19,485 $235,450 $14,204 $33,179 Equals: Net Income $63,978 - Calculate what margin the business requires for the year to cover extras: The business owner, or manager, must decide how much extra money above cost recovery/overhead is required, i.e. what the margin should be. It is best if each veterinary service contributes to the margin. Many veterinary businesses create a twelve month income (profit and loss) forecast incorporating anticipated increases in expenses for the next twelve months. A forecast for the case study example of Lamone and Yackaville is shown in Table 2. It is important to understand that the income (profit and loss) forecast does not specifically show monies for capital pay-down, owner drawings, or capital re-development; these must be covered by the forecasted profit (or profit margin). The important point when setting fees is that anticipated increases in outlay in the next year must be allowed for either in the overhead or in the margin.

Table 2. Example of a forecast Capital repayments Payout vehicle loan $17,800 Cover for contingency e.g. staff long service leave, maternity leave, hire costs of replacement staff Locum nurse to cover maternity leave, 6 months $32,500 Locum nurse to cover long service leave, 7 weeks $7,500 Other contingency e.g. increase in occupancy expenses $15,000 Increase staff remuneration Veterinarians productivity increases $5k x 4 $20,000 Nurses award increase x 5 $5,000 Nurses training Cert 4 $5,000 Business and staff development Ultrasonography training $5,000 Refurbishment of surgery $40,000 New signage, marketing and rebranding $40,000 Return to owners for money invested $185,838 current owner equity x 20% per annum $37,200 Total $225,000 - Calculate target professional services income for the year: As previously discussed, to support professional service provision annual income needs to be the sum of the annual overheads and the margin required, this is the target professional services income for the year, see Table 3 below.

Table 3. Target professional services income Overhead required for previous 12 months $934,174 Required additional margin for next year $225,000 Target total professional services income $1,159,174 -

Determine the realistic billable time for professional services: Often the largest single expense for a veterinary business is wages and salaries. In addition to this, for most veterinary businesses the veterinarian is the key charging unit, so overhead and required margin can be recovered only when work is charged to a client. Work charged is generally linked to the provision of veterinary knowledge and/or skills, and is thus veterinarian centric, i.e. dependent on the veterinarian being involved.

The average billing efficiency for a veterinarian is 50%, i.e. direct work:indirect work occur at approximately a 1:1 ratio. In very busy practices with many trained support staff, veterinary billing efficiency can reach 70%. As a comparison, the industry benchmark for agricultural consultants billing efficiency is 64% (C. Trengove, pers comm, 2013).

Each hour a veterinarian is at work may not be filled with actual billable work, or ‘direct work', as the veterinarian may be undertaking ‘indirect' work tasks such as: restocking vehicle; discussing a case with colleagues or laboratory' pathologists; writing newsletters or staff protocols; forward planning; or doing pro-bono work for wildlife or strays. The average billing efficiency for a veterinarian is 50%, i.e. direct work:indirect work occur at approximately a 1:1 ratio. In very busy practices with many trained support staff, veterinary billing efficiency can reach 70%. As a comparison, the industry benchmark for agricultural consultants billing efficiency is 64% (C. Trengove, pers comm, 2013).Calculation of direct work time in a year

Step 1: Calculate the total number of hours worked by all veterinarians in the year

Total full time equivalent veterinarians 4.5 FTE

Hours worked per week per FTE 38 hours

Yet each vet is only actually at work when:

Not on holidays (4 weeks)

Not at a conference (1 week)

Not on a public holiday (10 business days which is equivalent to 2 weeks)

Not sick (average sick days are 5 days per year so equivalent of 1 week)

Thus, a veterinarian is at work 44 full business weeks per year (52 - 4 - 1 - 2 - 1 = 44)

For Lamone and Yackaville Veterinary Practice the hours per year that veterinarians are actually at the workplace are:

4.5 x 44 x 38 hours/per year = 7,524Step 2: Apply a billable efficiency rate.

Assuming Lamone and Yackaville Veterinary Practice is typical of the veterinary profession and achieves 50% billing efficiency, i.e. direct:indirect work in a 1:1 ratiothe total billable hours of direct veterinary work in a year for Lamone and Yackaville Veterinary Practice are:

50% x 4.5 x 38 hours per week x 44 weeks at work/per year

= 3762 hours per year -

Calculate annual billable minutes for direct veterinary work: To calculate a per minute rate for professional fees, the target services income required (the sum of the overhead and the required margin) is spread over the direct (billable) time in minutes for the same period.

Example: Lamone and Yackaville Veterinary Practice 1st July 2013 - 30th June 2014

Target Professional Services Income = $1,159,174

Total billable minutes of direct veterinary work in a year is:

60 x 3762 hours per year= 225,720 billable minutes of direct veterinary work/year

So, Target Professional Services Income = $1,159,174/225,720 = $5.14 per minute

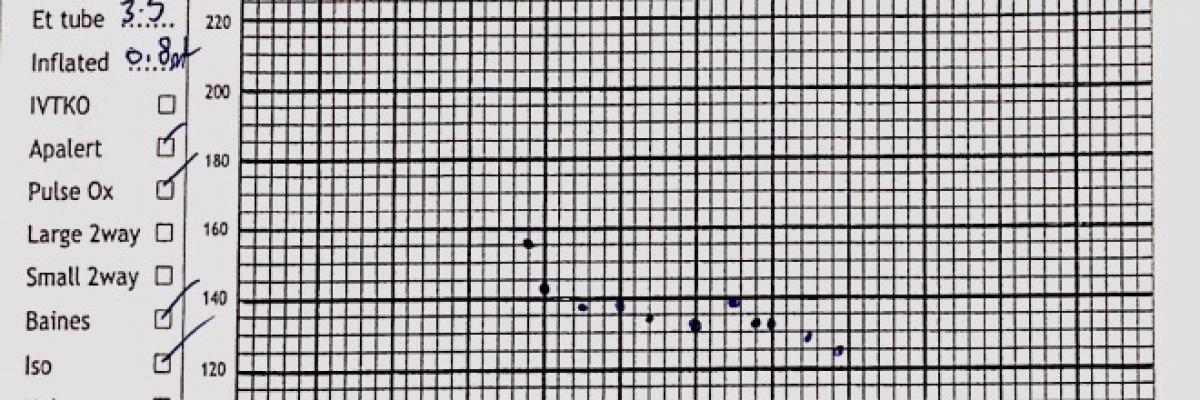

Billable minutes of direct workThe per minute rate can now be multiplied up to suit particular veterinary services, as long as it is known how long on average it takes to provide the service. Using a calculated per minute rate, a veterinary practice can create a fee schedule for professional services based on realistic times for veterinary input using the cost-plus method. Time records for surgical procedures can usually be gained by observation or research of available data. It is usually a straight forward exercise to access 12 months of anaesthetic record sheets and create a spreadsheet so that minimum, maximum and average times can be calculated for different procedures. In Figure X the anaesthetic record shows the time the cat was induced, the time the veterinarian made the incision, the time the veterinarian ended the surgery and the time the cat had the endotracheal tube removed. Analysis of a series of anaesthetic records can yield a great deal of information on which pricing of anaesthesia and surgeries can be based.

Anaesthesia record

Time records for non-surgical work can be acquired by observational studies, and examination of the appointment diary. The aim is to determine average times for various direct veterinary services. When the time for each veterinary service is known, fees can be set using the per minute rate.

Table 4, below, shows example fees for a veterinary practice.

Table 4. Examples of fees determined using cost plus method of fee setting Professional service Components Price based on cost-plus method Consultation - Small animal 15 mins $77 Annual health check and vaccination 15 mins plus $30 for C5 vaccination $107 Surgery rate per minute $5.14

Consultation - Large animal 30 mins $154 Pregnancy testing per hour $308

Examination for mortality insurance 30 mins: 25 mins with horse and 5 mins paperwork $154 Note the above example is based on the following specifics: wages per vet are a combination of new graduates and experienced veterinarians 50% billing efficiency for time on site and there are 4.5 full time vet equivalents.

- Determine annual overhead: Total annual overhead is the total of all fixed costs for a twelve month period. Fixed costs are costs that are essential to the business such as rent, wages and electricity. The total annual overhead does not include variable cost items which are items that are typically ordered when needed, and do not necessarily need to be purchased to keep the business operational, such as stock and external services. The business' most recent twelve month Profit and Loss Financial Statement contains cost and expense lines, which can be divided into variable costs and fixed costs (overhead), see Table 1.

-

Compare calculated fees to current fee schedule - is the practice setting realistic fees?

The cost-plus method can be used to evaluate a set fee schedule; i.e. be a reference for pricing decisions. Comparison of the fee schedule to the cost-plus fees calculated using the per minute rate is an important determinant of whether the fee schedule accurately reflects the cost of service provision.

Table 5, below, provides an example of the comparison of a current fee schedule to fees calculated using the cost-plus method for the example Veterinary Practice.

Table 5. Example comparison of fees calculated by the cost plus method to fees in a practice's fee schedule Price based on cost-plus method Price as per fee schedule Consultation - small animal $77 $53 Canine annual health check and vaccination $107 $83 Surgery rate per minute $5.14 $8.00 Consultation - large animal $154 $160 Pregnancy testing per hour $308 $320 Mortality insurance examination $154 $160 -

Flow on effects of discounted fees

Consider that a business has decided to discount common veterinary services. The business should consider how much the fees for other services must be inflated for to compensate for discounting. Can sufficient services with inflated prices be performed to make up for losses on discounted procedures?

See Table 6 for an illustration, across a small number of fees, of the magnitude of deficits or gains once the difference between the cost-plus calculated fee and the actual fee is multiplied up by the actual quantity of a particular service charged over one year.

Table 6. Example of the effects of discounting common veterinary services Price - based on

Cost-Plus MethodPrice - as per

fee scheduleDifference between

Cost-Plus and Fee ScheduleQuantity of services

per yearOverall loss

or gainConsultation - small animal $77 $53 - $24 2,000 consultations - $48,000 Canine Annual Health Check and C5 Vacc $107 $83 - $24 2,000 health checks & vacc - $48,000 Surgery rate per minute $5.14 $8.00 + $2.86 5,000 minutes + $14,300 Consultation - large animal $154 $160 + $6 300 consultations + $1,800 Pregnancy testing per hour $308 $320 + $12 200 hours + $2,400 Mortality insurance examination $154 $160 + $6 20 examinations + $120 -

Pricing decisions

There are three major influences on pricing decisions:

- costs

- competitors

- clientele

Prices may be adjusted for a variety of reasons, some of which are:

- in line with the strategic plan for the practice

- further detail is utilised to price various fees, for example, the business may allocate overhead in different proportions for different activities. For further information see Activity Based Costing in Ackermann (2007) or Horngren et al. (2011)

- client factors which may affect price sensitivity for a service or procedure.

Price sensitivity relates to client demographics. A demographic is considered to be price sensitive when clients of a particular demographic respond to price increase by seeking a service provider with lower prices. Alternatively, a client demographic may be price insensitive which means that price can increase as clients are willing to pay for the service. A practice is likely to choose to be a high volume, low cost practice in an area with a demographic for which pet care is price sensitive. A practice can aspire to be a low volume, high quality practice when the serviced demographic is price insensitive.

A practice may inflate some fees to deliver margins well above the desired margin, and discount other fees. Reasons to markedly inflate some fees above a standard cost-plus fee include:

- to compensate for emergency response needed for the task, thus loss of other work which may be cancelled or delayed

- to compensate for drugs and equipment that need to be available to enable emergency or infrequent response and are not be used on a regular basis, i.e. loss or delay of cost recovery

- to compensate for staff training to ensure proficiency for an infrequent task

- to compensate for the fact that other prices have been discounted to or below break-even point, i.e. loss leaders, as discussed below

- price sensitivity of the client demographic will not bear the fee at the higher level, i.e. client ability to pay - it is better to receive some income, rather than none

Reasons that a practice may heavily discount a fee include:

- promotional purposes (e.g. to bring new clients who may form relationships with the practice)

- community service purposes

- high turnover services or sales

When a business discounts a fee to below cost to attract new clients in the hope they will become regular clients or make other purchases, it is termed a ‘loss leader'.

The core business of a veterinary practice is the conversion of knowledge and skills of the team into professional services charged to the client through fees. As such, professional fees should contribute significantly to the profit margin, and variable items, such as pathology, drug sales, and product sales, should not be relied upon to support the viability of the business. An illustration of how to determine the relative contribution to the overall profit margin of professional services and product sales can be found in the topic notes for Veterinary Business KPIs (see the annual KPI review example for the case study practice, Lamone and Yackaville Veterinary Practice).

Some large animal practices choose to break even or lose on professional fees and make up for the loss on drug sales. It is not uncommon for large animal or mixed practices to actually inadvertently do this if they have not used a cost-plus or activity based method for pricing. Large animal practices are then vulnerable when a client can request a prescription from the attending veterinarian and have the prescribed drugs supplied by a pharmaceutical outlet (this is now legislation in New Zealand).

At the far end of the spectrum, many feedlot veterinary consultants earn their income only from mark-ups on drug sales to clients, and do not charge professional fees at all. Yet, one may expect that the aim of the veterinarian is to optimise animal health and aim for minimal drug use.

Regardless which sector of veterinary business you are in, it is wise to think critically and reflectively about pricing methods and decisions. Pricing decisions affect the sustainability of a business and should be arrived at with more thought than just what nearby practices are charging, as they are very likely to be operating at less than satisfactory margins as they may be discounting in efforts to attract more business.

- staff education, for example, investment in orthopaedic training for a practice partner

- marketing and business promotion, and

- upgrade of facilities, for example, renovation of surgery suite, extension of building, or purchase of digital xray.

- interest at the bank for savings is 4%

- stock market gains on money invested can be in the order of 10% over a 10 year period

- commercial rental properties in a high profile location generally return 8 - 12 % on the value of the property

- residential rental properties generally return 4 - 8% on the value of the house

- interest rate to borrow monies for home loans is 5%

- interest rate to borrow monies for business premises or equipment is around 6%

- overdraft interest rates are around 7%

- credit card interest rates are 12 - 19.9%

-

More about margins

The margin is important because without extra earnings above overhead cost recovery, i.e. above break-even point, there is no extra money for the business to use to cover further cash flow needs in the next year. Categories of further cash needs include:

- capital repayments to reduce loans

- cover for contingency (e.g. staff long service leave, maternity leave, cost of replacement staff)

- increases in remuneration for staff

- business and staff development

- return to owners for money they have invested

Each of these categories of further business needs are discussed below.

Capital repayments to reduce loans

Most businesses need to borrow money to enable purchase of the business, business premises, or upgrades of facilities or equipment. The amount of money borrowed is called capital (or principal). The borrower-lender contract details how capital is repaid to the lender. The timing of capital repayment may be at the end of the loan period or on a regular basis during the loan period. Nonetheless, the capital must be repaid, and should come from business income.

Cover for contingency

Businesses have expenses which may, or may not, be the same each year. Expenses may gradually increase, or some particular expenses may spike.

For example, after a new business completes its growth phase, it is not uncommon to experience a wave of staff long service leave becoming due. Similarly, businesses can experience a run of leave needs for maternity and sick leave.

Though these are a normal part of business, stress can be placed on cash flow and profitability when such events are not accounted for in contingency planning.

There are also associated costs of recruiting, training and paying wages of replacement staff at the same time as paying leave entitlements to long term staff members.

Increases in remuneration for staff

Staff pay rates generally increase at a rate per year that is linked to the national Consumer Price Index (CPI).

In addition, staff, especially those who demonstrate greater skill acquisition, can create greater productivity for the business and as a result may be given a wage increase. Thus, a sufficient margin over cost recovery is required in fees charged to clients, or a business will not have sufficient extra money to increase wages for permanent staff.

Business and staff development

Business and staff development activities should be planned for in a business development plan and include considerations, such as:

Return to owners for invested money

Owners of a business invest money to start the business, and may leave money in the business rather than use it for other purposes. Leaving money in the business is effectively a decision to further invest in the business, as otherwise the money could be extracted and invested elsewhere. It is therefore important that income generated by fees for services not only covers business running expenses, but also allows extra money to compensate for the owner's money being invested in the business.

The amount of compensation an owner should aim to receive on money they have invested in a business should be the same or greater than returns likely on other investment options. For example, at the time of writing this document:

What return on investment is appropriate for veterinary practice owners? Consider your savings are invested in a veterinary practice, what return for the risk would you be comfortable with? You may be able to earn 4.5% on money in the bank and this is a very safe investment. Would you prefer 10%, 20% or 30% from a small business investment, considering that 30% of Australian small businesses fail in the first five years. Why might you want a higher than 4.5% return on your investment? Does the degree of risk affect the rate of return you require to put your money into a business?

At the time of writing this document, with interest rates at historically low levels, a business owner should seek to earn a minimum of 10 - 12% return on investment. Compare this with the early 1990's when interest rates for borrowing were very high at 18% for business loans, and interest obtainable for money deposited at the bank was approximately 14%, an owner would be looking to earn a minimum of 20% return on investment.

For the degree of risk in investing into micro (<10 employees) and small (<100 employees) businesses, ideally an owner should be aiming to make 20 - 25%.