Centre for the Subatomic Structure of Matter

The Special Research Centre for the Subatomic Structure of Matter (CSSM) carries out research in theoretical nuclear and particle physics.

Our aim is to make advances in our understanding of the structure of subatomic matter and establish a sound and consistent theoretical framework. We integrate theory and experiment to allow a variety of attacks on the problem so that progress can be made more rapidly than by a set of isolated projects.

The Centre has an emphasis on the Strong Interactions and their importance in determining the nature of matter. The Strong Interactions are described by the quantum field theory, called quantum chromodynamics (QCD), which governs the interactions between quarks and gluons.

In studying the Strong Interaction, we explore the Standard Model of nuclear and particle physics and its role in explaining the nature of hadronic matter. The topics of interest range all the way from individual hadrons to atomic nuclei, and ultimately the most dense matter in the Universe in the core of neutron stars.

We are working to clarify further the behaviour of the microscopic world through a variety of complementary techniques, including:

- supercomputer simulations of fundamental quantum theories (such as QCD);

- effective field theory calculations; and

- building models that capture the essential degrees of freedom in complex systems (such as the quark-meson coupling model).

International Lattice Data Grid

The CSSM acts as the regional grid for Australia within the International Lattice Data Grid (ILDG) , a worldwide effort to make valuable data sets from lattice QCD simulations available throughout the international scientific community.

Research notes

-

Hint of the Existence of a BSM Particle: A Dark Photon

Published in the Journal of High-Energy Physics

The existence of dark matter has been firmly established from its gravitational interactions, yet its precise nature continues to elude us despite the best efforts of physicists around the world. The key to understanding this mystery could lie with the dark photon, a theoretical massive particle that may serve as a portal between the dark sector of particles and regular matter.

In our recent work - a collaboration between CSSM, the Adelaide node of the ARC Centre of Excellence for Dark Matter Particle Physics and Jefferson Laboratory - we study the potential effects a dark photon could have on the interpretation of existing experimental results from the deep inelastic scattering process.

Specifically, we make use of the state-of-the-art Jefferson Angular Momentum collaboration (JAM) global analysis framework for parton distribution functions, modifying the underlying theory to allow for the effect of a dark photon. We show that the dark photon hypothesis is preferred over the Standard Model hypothesis at a significance of 6.5 sigma, which constitutes strong evidence, albeit indirect, for a particle discovery.

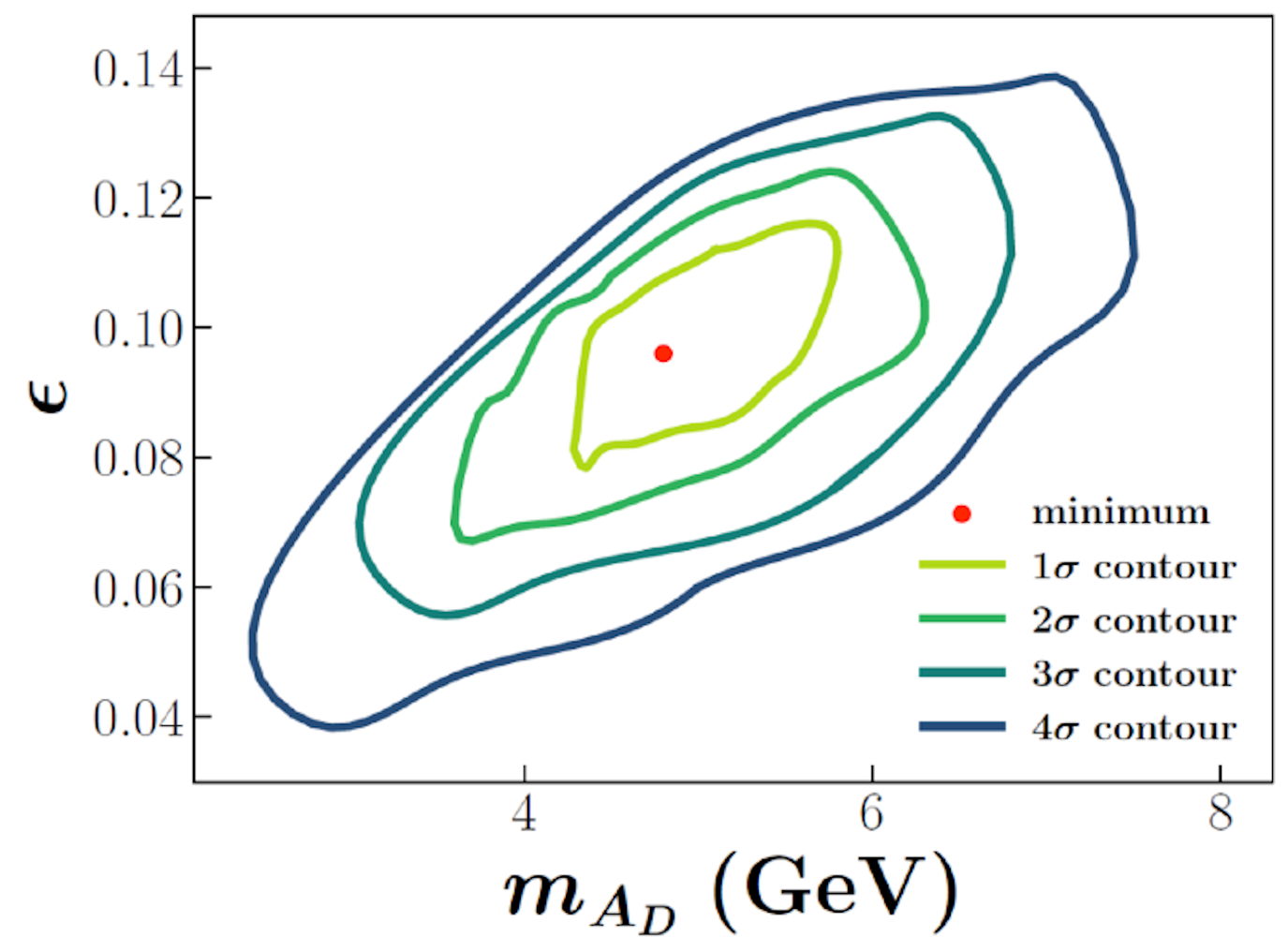

Profile likelihood showing preferred regions for the dark photon mass and mixing parameter. This suggests that the Standard Model is disfavoured at 6.5σ.

-

Sensitivity of Parity-violating Electron Scattering to a Dark Photon

The ARC Centre of Excellence for Dark Matter Particle Physics (CDMPP) aims to discover what this mysterious stuff, dark matter, is made of. It is five times as plentiful as the baryonic matter we have explored so successfully, and of which we are composed. We do not know what kind of particle it is, but we (along with a very large number of people around the world) want to understand this. One key approach is the SABRE experiment that is being built in a new laboratory in a gold mine (1km underground) in Stawell, which will hopefully shed light on this question in a few years.

The present work, published in Physical Review Letters1, explores the possibility that dark matter is in the form of a dark massive photon. In particular, we explore the discovery potential of the new tool enabled by the upgrade at Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility (JLab) in the United States.

This new tool is parity-violating electron scattering. Parity violation is, simply put, the difference between what happens in the laboratory and what happens when you view the experiment in a mirror. The differences are very small, typically less than a part per million, but incredibly precise measurements enable us to observe this and use it as a signal of the existence of this new particle.

We show that the effects of this new particle may reconcile a surprising discrepancy between the neutron density in a lead nucleus inferred from the PREX experiment at JLab, and that predicted by nuclear structure theory. We also show that there may be corrections as large as 10% in the valence quark distributions extracted from data taken at HERA in Germany. Finally, it is shown (see figure below) that a future experiment comparing electron and positron deep inelastic scattering on the deuteron could provide a vital test of the existence of such a particle.1 A. W. Thomas, X.-G. Wang and A. G. Williams, Physical Review Letters 129 (2022) 011807

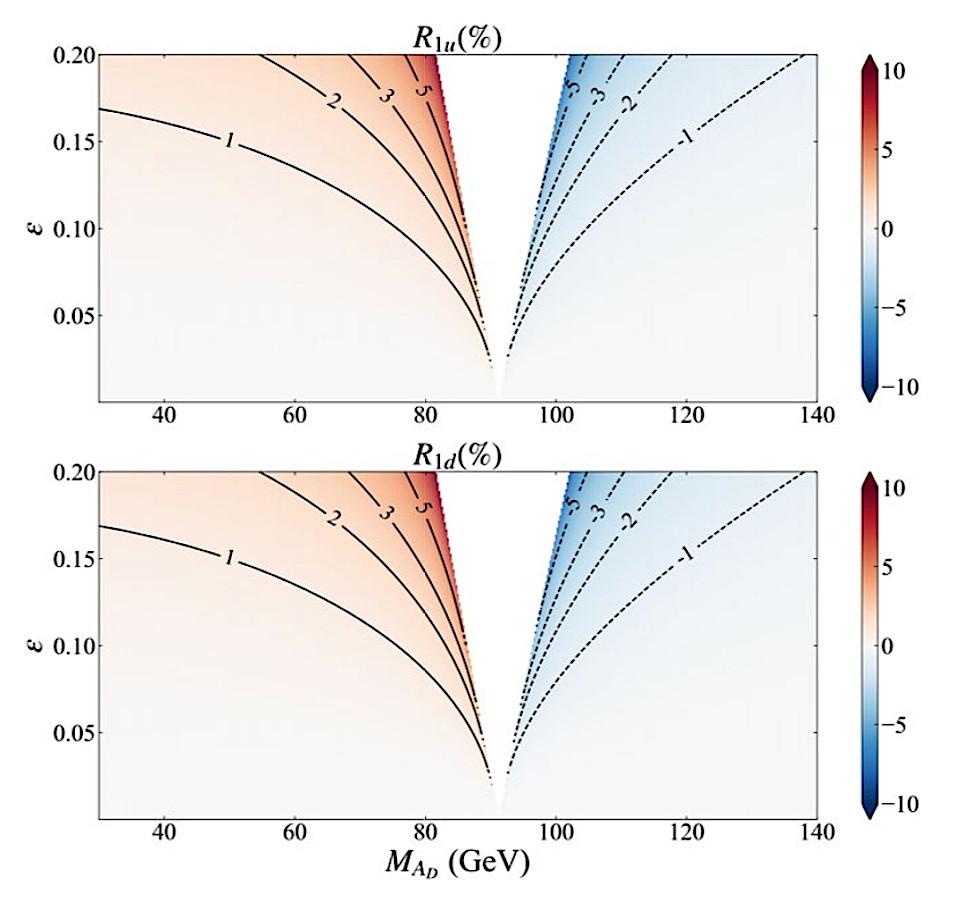

Relative size of the correction to the measured distance in the cross-section for electron versus positron scattering from the deuteron.

-

Isovector EMC Effect from Global QCD Analysis with MARATHON Data

After two decades of planning, the MARATHON experiment at Jefferson Laboratory has provided intriguing hints about the mysterious modifications of protons and neutrons in mirror nuclei.

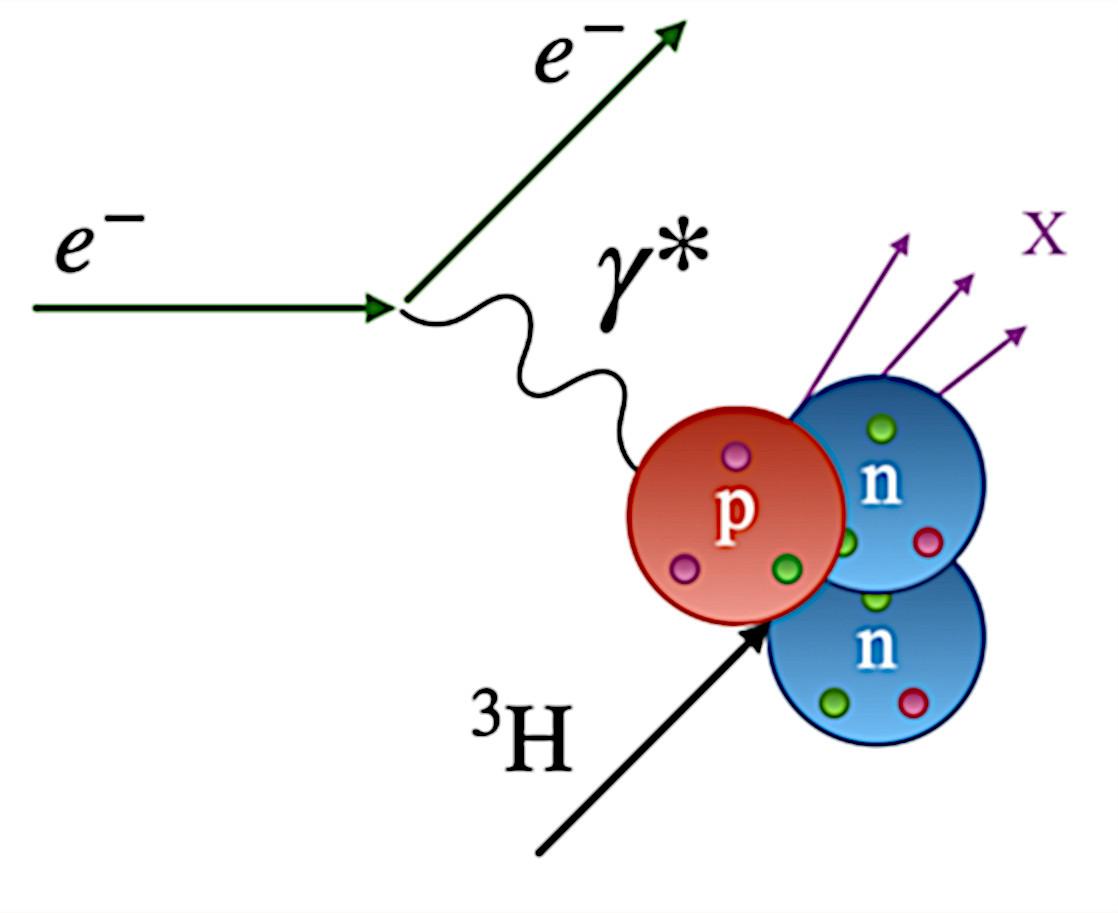

The name of the experiment has two possible interpretations: the Greek origin of the scientist driving the work, Makis Petratos at Kent State University, or perhaps simply the stamina needed to drive the experiment to a successful conclusion over such a time frame. The experiment involved the use of a tritium target at Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility (Jefferson Lab). Tritium is extremely dangerous and so the experiment involved very careful safety protocols.

Tritium is an isotope of hydrogen with one proton and two neutrons. It is a “mirror” copy of the helium-3 nucleus which has two protons and one neutron. That symmetry, along with calculations carried out in the CSSM with a student, Francois Bissey, and a colleague at Flinders University (Iraj Afnan), motivated the experiment.

The original aim was to accurately measure the distribution of quarks, especially the down quark, as a function of momentum. The dependence of the ratio of down quarks to up quarks, d/u, on the fraction of the proton’s momentum is a fundamental property which has defied measurement ever since quarks were discovered 50 years ago. It tests our understanding of QCD, the fundamental theory of the strong force.

Analysing data from mirror tritium and helium nuclei, Cocuzza et al. reported opposite modifications for up quarks versus down quarks. This constitutes the first experimental clue for an isovector EMC effect - where changes within a nucleus depend on isospin - for light nuclei.

This analysis of the Marathon data provided the first experimental hint for the existence of this isovector EMC effect, where changes within a nucleus depend on isospin. It will certainly inspire a great deal of further experimental effort, which ultimately will tell us whether we really do have a new paradigm [1] for the way atomic nuclei are built.

[1] A. W. Thomas, “Role of Quarks in Nuclear Structure”, Oxford Encyclopaedia of Science, July 2020: https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190871994.013.1

Published in: Physical Review Letters 127 (2021) 24, 242001

Published: Dec 6, 2021DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.127.242001

Credit : Christopher Cocuzza

-

Quantum Technologies Theory Group

The Quantum Technologies Theory Group specialises in applying quantum mechanics to emerging and future technologies.

Applications of quantum mechanics have ranged from electronics (transistors: without which there would be no modern electronics, such as mobile phones, laptops etc.), to medicine (both imaging (MRI and PET scans), and treatment (such as laser surgery, and cancer treatment- including recent advances in proton therapy)), to civilian infrastructure (nuclear power and Maglev trains).

Recent advances in generating entangled photons, cold-atom interferometry and quantum sensing have the potential to develop further life-changing technologies.

The Quantum Technologies Theory Group focuses its research on finding novel ways to apply the theory of quantum mechanics to practical situations.

Research:

- quantum radar

- quantum clock synchronisation

- target tracking

Group members:

- Dr. Samuel Drake : Senior Research Scientist, Quantum Technologies Group, DST Group

- Prof. Anthony W. Thomas FAA : Elder Professor of Physics, CSSM, Physics Department, University of Adelaide

- Doc. Dr. Ayse Kizilersu : Senior Research Associate, CSSM, Physics Department, University of Adelaide

- Dr. James Quach : Ramsay Fellow, IPAS, Physics Department, University of Adelaide

-

Measuring the weak charge of the proton

With the announcement of the detection of the Higgs boson in 2012, observation of the full suite of particles predicted by the Standard Model finally was complete. However, despite that success, the Standard Model does have its limitations. Various phenomena, including gravity, dark matter, dark energy, and the matter/anti-matter asymmetry, remain unexplained by the Standard Model. Thus, the search for Beyond-the-Standard-Model physics (BSM) continues.

One search method concerns the production of new particles by high-energy accelerators; any such particles, by definition not predicted by the Standard Model, will be indicative of the presence of BSM physics. This is a direct method of exploration which, thus far, has not resulted in any new particles.

Another approach is to use some indirect method - look for something which, whilst based on observations of SM particles or other observable phenomena, allows one to make predictions relevant to BSM physics.

As part of the Jefferson Lab Qweak collaboration, the CSSM's Associate Professor Ross Young has contributed to the first successful high-precision measurement of the weak charge of the proton. The proton's weak charge determines how strongly a proton will interact with other particles via the electro-weak force, one of the four fundamental forces within the Standard Model framework.

The very precise experimental value obtained for the proton's weak charge allows researchers to place very strong constraints on certain types of interactions that are not described by the Standard Model, thus providing a predictive capability within the context of as-yet unobserved BSM phenomena, particularly towards higher particle masses.

The work is described fully in Nature, and in a more condensed manner on the Faculty of Sciences news blog.

The reduced asymmetry 𝐴𝐞𝐩/𝐴0=𝑄𝐩𝐰+𝑄2𝐵(𝑄2,𝜽=0) versus Q2

-

Novel constraint on dark matter hypothesis

For some years there has been a 3.5 standard deviation discrepancy between two methods of measuring the lifetime of the neutron which, in free space, is a little over 14 minutes. In an exciting paper earlier this year, Fornal and Grinstein proposed that the explanation might lie with dark matter, with only one of the methods of measurement sensitive to a hidden decay mode where a neutron decays to dark matter plus something.

Nuclear constraints mean that the dark matter mass would have to be within roughly one percent of the mass of the neutron. This proposal was particularly timely, as it was followed closely by an article in Nature suggesting the need for a dark matter particle with a mass below twice the neutron mass.

A collaboration involving staff of CSSM (Theo Motta and Anthony Thomas) and the CEA in France (Pierre Guichon) realised that such a particle may well have consequences for the properties of neutron stars, as neutrons high in the Fermi sea in the dense matter at the core of a neutron star would decay to dark matter particles with much lower energy and pressure.

Indeed, their calculations showed that (as illustrated in the figure below), for weakly interacting dark matter, this decay process would dramatically reduce the maximum mass of a neutron star, to just 0.7 solar masses, which is way below the range of masses of observed neutron stars .

As a consequence, one is led to reject the hypothesis that the neutron has this hidden decay mode.

Comparison of the mass-versus-radius curves resulting from the solution of the TOV equations for the case where only nucleons are allowed and where dark matter is included. The reduction in the maximum possible mass is dramatic, from around 2.2 M⊙ to just 0.7 M⊙.

Read the full text here.

-

Coulomb sum rule

For more than 80 years, the atomic nucleus has been viewed as a weakly-bound collection of protons and neutrons.

However, with the discovery that the proton and neutron are themselves composed of more fundamental particles known as quarks, scientists have wondered whether their quark structure might change when the protons and neutrons are located inside a nucleus as compared with when they are unbound.

It has been suggested that such a change might be crucial in understanding nuclear binding. As well as exploring the consequences of this idea for the properties of atomic nuclei, it is vital to search for experimental tests.

Bentz, Cloët and Thomas have predicted a remarkable signal of this anticipated change in structure. If confirmed by an experiment performed at the Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator facility in Virginia (USA), which is expected to announce results soon, this would herald a new paradigm for the structure of atomic nuclei.

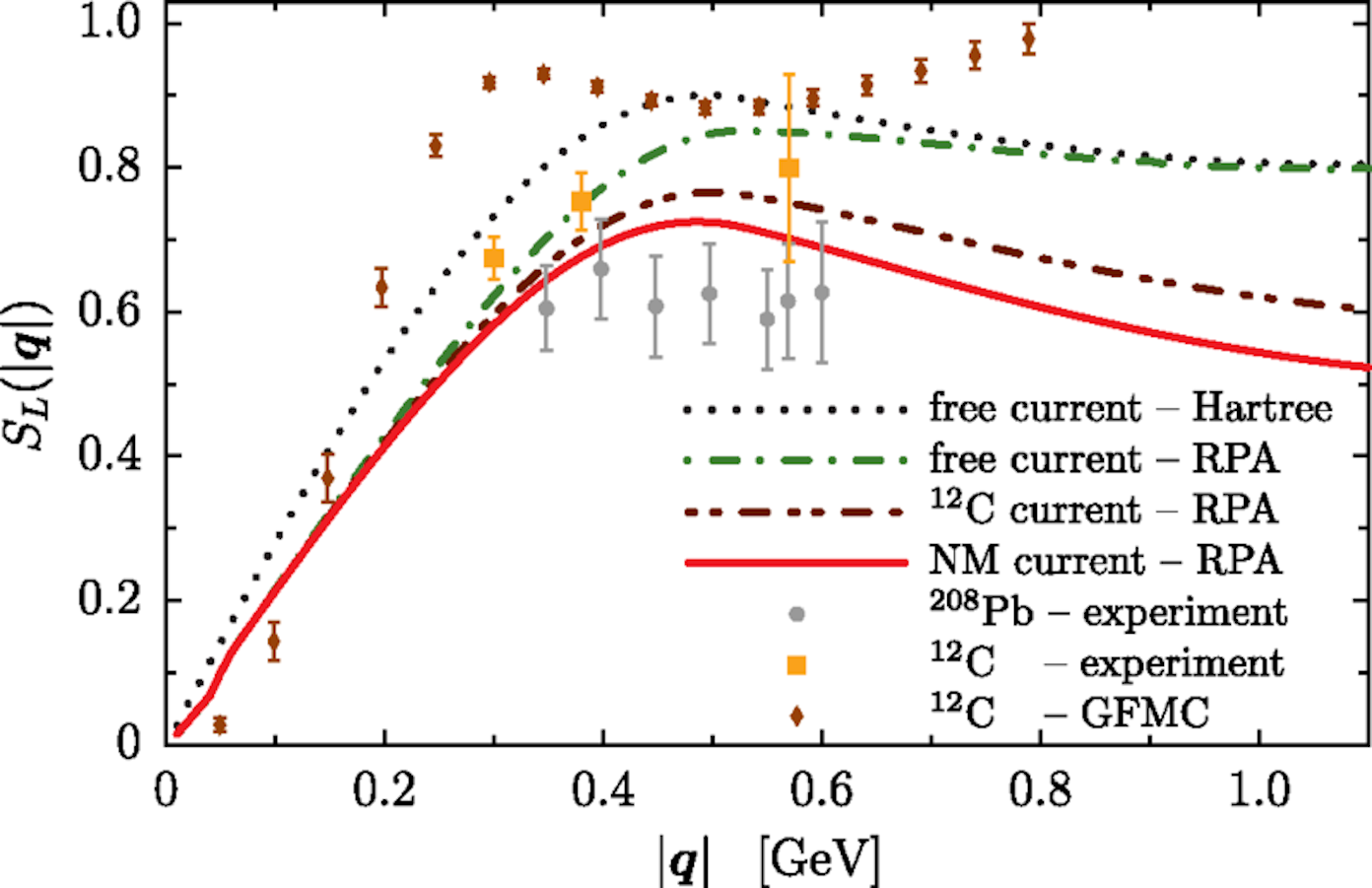

This figure illustrates the Coulomb sum rule for nuclear matter with a density consistent with that of 12C (carbon) and 208Pb (lead).

It illustrates the role of relativistic effects but most importantly, at large three-momentum transfer (larger |q| values), a reduction of up to 20% in C(|q|) (red solid curve compared with the green dash-dot) resulting from the in-medium modification of the proton electric form factor.

-

Baryon's innards have molecular structure

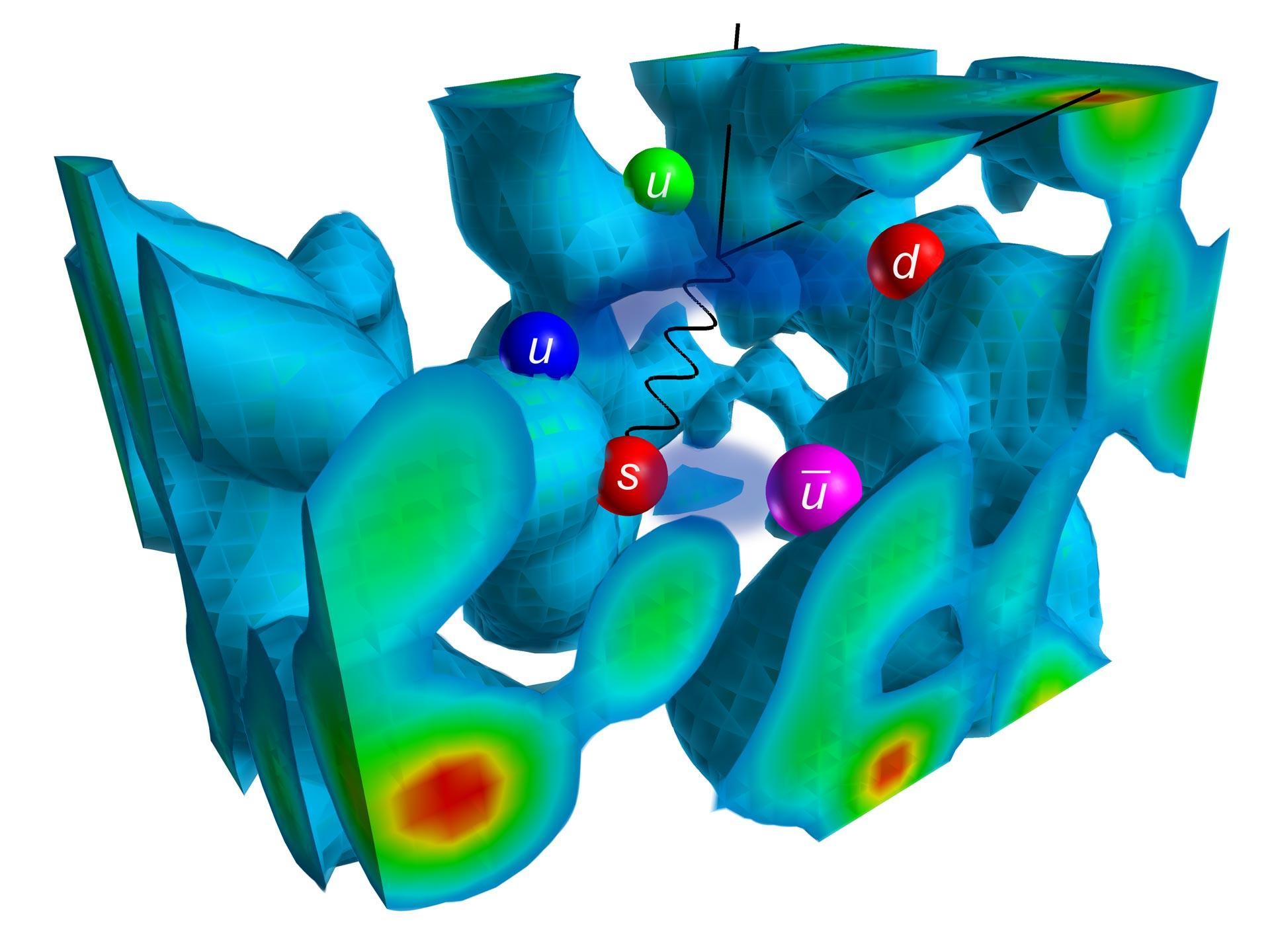

In its excited state, the Lambda baryon behaves like a molecule, according to new lattice QCD simulations of the particle’s magnetic structure carried out at the CSSM.

Graduates of Particle Physics 101 know that baryons are made of three quarks. An excited state of the Lambda baryon, the Λ(1405) appears to defy this simple description: the particle behaves like a 'molecule' made of a quark pair in the form of a meson and a quark triplet in the form of a baryon. This picture, which can’t be explained by the standard quark model, has been debated for almost fifty years. Now the molecular picture has been resolved via first principles calculations by theorists at the University of Adelaide.

What’s puzzling about the Lambda baryon - a bound state of an up, down, and strange quark - is that much less energy is needed to excite it than is expected for three bound quarks.

The molecular picture explains the difference by assuming that the excitation produces two compound particles: an antikaon (composed of a strange quark and an anti-up or anti-down quark) and a nucleon (a proton or neutron). This system of five quarks is more strongly bound than three bare quarks.

In the past, theoretical calculations haven’t been able to convincingly predict the Λ(1405)’s internal structure because they approximated, via models, the quantum field theory that describes quarks.

Professor Derek Leinweber and his colleagues tackled the problem with lattice quantum chromodynamics (QCD), which uses supercomputers to simulate quark theory. The authors calculated the strange quark’s contribution to the Λ(1405) magnetic moment and found it was zero - the value expected if the strange quark is bound in an antikaon which, in turn, is bound to a nucleon.

The finding is a strong sign that the structure of the Λ(1405) is dominated by an antikaon-nucleon molecular structure. In other configurations, the authors emphasise that the strange quark would have a non-zero magnetic moment.

More information

A visualisation of the structure of the Lambda 1405 baryon resonance

The energy density of a typical gluon field fluctuation found in the QCD vacuum is illustrated. Its lumpy structure, representative of the underlying instanton-like field configurations, attract the quarks of the Lambda 1405.

Here the up, down and strange (u, d and s) valence quarks of the Lambda 1405 are complemented by an up-anti-up (u − u-bar) quark pair. A flux tube between the s and anti-u quarks indicates the formation of a K - meson while the remaining quarks (u, u, d) are bound to a proton with the Y-shape flux tube. Together, these form the molecular bound state of the Lambda 1405.

An electron (solid line) scatters off the strange quark through the exchange of a photon (wavy line), providing information on the strange magnetic form factor of the Lambda 1405.

-

Structure of finite nuclei starting at the quark level

Traditional nuclear theory starts with non-relativistic two- and three-body forces, and concentrates on solving the many-body problem as accurately as possible. For medium- and heavy-weight nuclei, the most successful tool is the density functional approach, which is based upon purely phenomenological, density-dependent Skyrme forces.

Only recently has it been possible to go to a more fundamental level and derive a density-dependent effective force starting at the quark level.

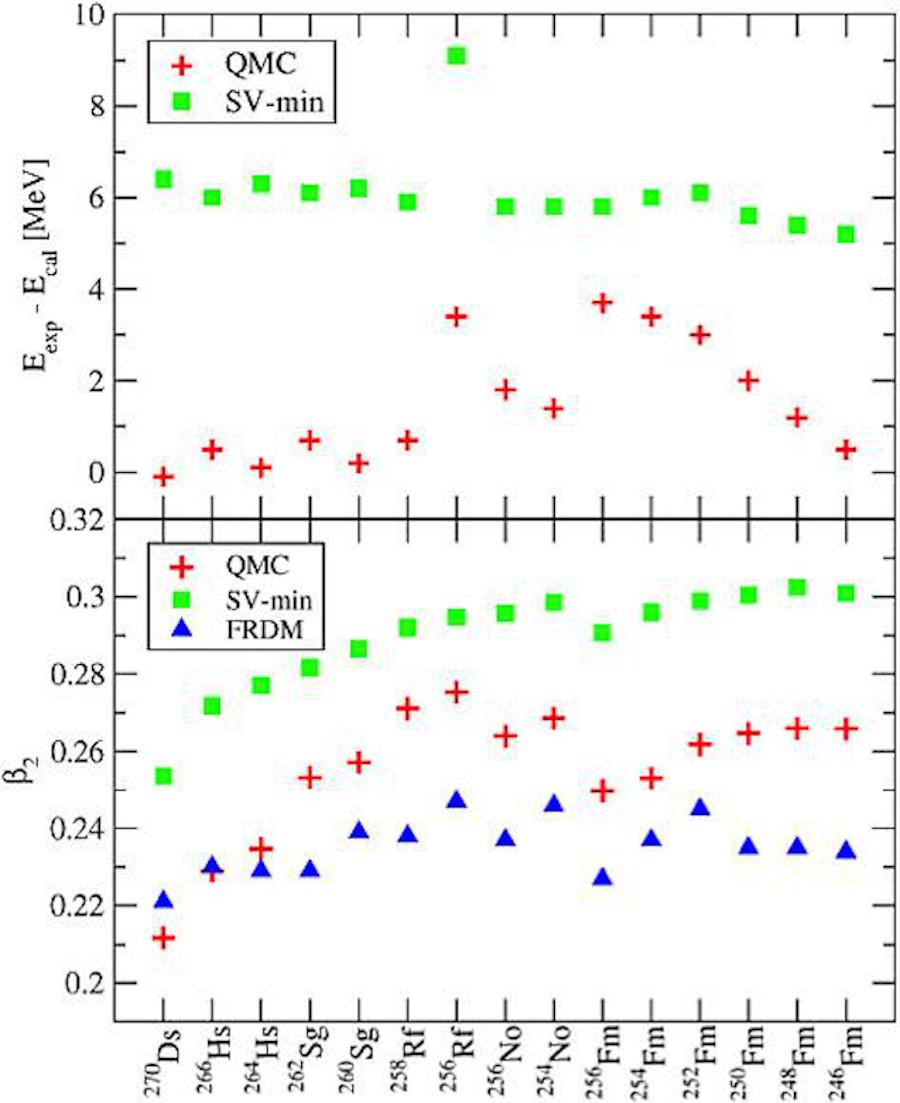

Now, for the first time, this derived force has been systematically applied to the properties of finite nuclei across the Periodic Table. With a far smaller number of parameters (the σ, ω and ρ couplings to the light quarks) for the effective force and the traditional two pairing parameters, the binding energies of a sample of more than one hundred nuclei across the entire Periodic Table were reproduced within 0.35%.

Another notable successes of this initial study of the QMC Skyrme force was the prediction of shape co-existence between oblate, spherical and prolate shapes in Zr, with N=60 being a critical transition point. It also predicted a double quadrupole-octupole phase transition in the Ra-Th region.

We expect to see many applications and developments of this model in the next few years. This is especially interesting in the light of the number of new rare ion facilities worldwide.

This figure illustrates the predictions for superheavy nuclei, where the binding energies (which were not fitted) [upper panel] were reproduced with an accuracy of 0.1% and the deformations [lower panel] were also extremely well described.

-

Visualisations of quantum chromodynamics

As a key component of the Standard Model of the Universe, Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD) describes the interactions between quarks and gluons as they compose particles such as the proton or neutron.

The CSSM has developed collection of visualisations of QCD developed by Professor Derek Leinweber, available on our YouTube channel. State-of-the-art order a4-improved lattice operators are used in creating the animations, including the three-loop improved lattice gauge action and the five-loop improved lattice field strength tensor.

The animations illustrate the typical four-dimensional structure of gluon-field configurations averaged over in describing the vacuum properties of QCD. The volume of the box is 2.4 by 2.4 by 3.6 fm, big enough to hold a couple of protons. Contrary to the concept of an empty vacuum, QCD induces chromo-electric and chromo-magnetic fields throughout space-time in its lowest energy state.

After a few sweeps of smoothing the gluon field (50 sweeps of APE smearing), a lumpy structure reminiscent of a lava lamp is revealed. This is the QCD Lava Lamp. The action density s similar to an energy density, while the topological charge density is a measure of the winding of the gluon field lines in the QCD vacuum.

The first animation was featured in Professor Frank Wilczek's 2004 Nobel Prize Lecture.

Two frames from an animation showing energy density variations of the gluon field in a vacuum.

-

Quantum chromodynamics and high-performance computing

Professor Derek Leinweber discusses lattice QCD and the origin of mass, and the importance of world-class HPC facilities.

QCD visualisations

Empty space is not empty... it's filled with the quark and gluon fields of Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD), the quantum field theory of the strong interactions governing the structure of subatomic matter.

Staff and students use data visualisation of the results of their simulation and modelling code to present those results in a manner that greatly assists the interpretation of those data. Presented here is a selection of these visualisations.

Please visit our Youtube channel for more examples.

CSSM history

The centre began official operations in 1997 as a result of a national proposal by Professors Anthony W. Thomas and Anthony G. Williams for one of eight Commonwealth Special Research Centres, with funding for a period of nine years.

There was one competitive round for Special Research Centres across all fields of research every three years resulting in approximately two dozen such centres nationally at any one time. The CSSM is currently administered through the Discipline of Physics in the School of Physics, Chemistry and Earth Sciences.

During its lifetime, the CSSM has developed a very strong international reputation as a major contributor in its area, and has held, or taken part in, many workshops and conferences.

People

- Please see the main NUPP page for a list of personnel within Nuclear and Particle Physics.

- CSSM staff and students will be listed as "CSSM" under the Area item in their entry.

Contact

Tel: +61 831 33533

Email: cssm@adelaide.edu.au

Location:

Room 126, Physics Building, North Terrace campus, University of Adelaide

Page author and maintainer: Dr. Padric McGee