They're strange, alien-like creatures from the Flinders Ranges - but how do they eat?

University of Adelaide scientists have discovered the feeding mode of Pentaradial Arkarua, a strange, alien-like creature that once roamed the Flinders Ranges.

This creature inhabited tropical, shallow waters covering the Flinders Ranges of South Australia 555 million years ago, according to a team of international researchers involving Associate Professor Diego García-Bellido from the South Australian Museum and the University of Adelaide's Environment Institute and School of Biological Sciences.

Illustration: Ediacara Biota by Peter Trusler

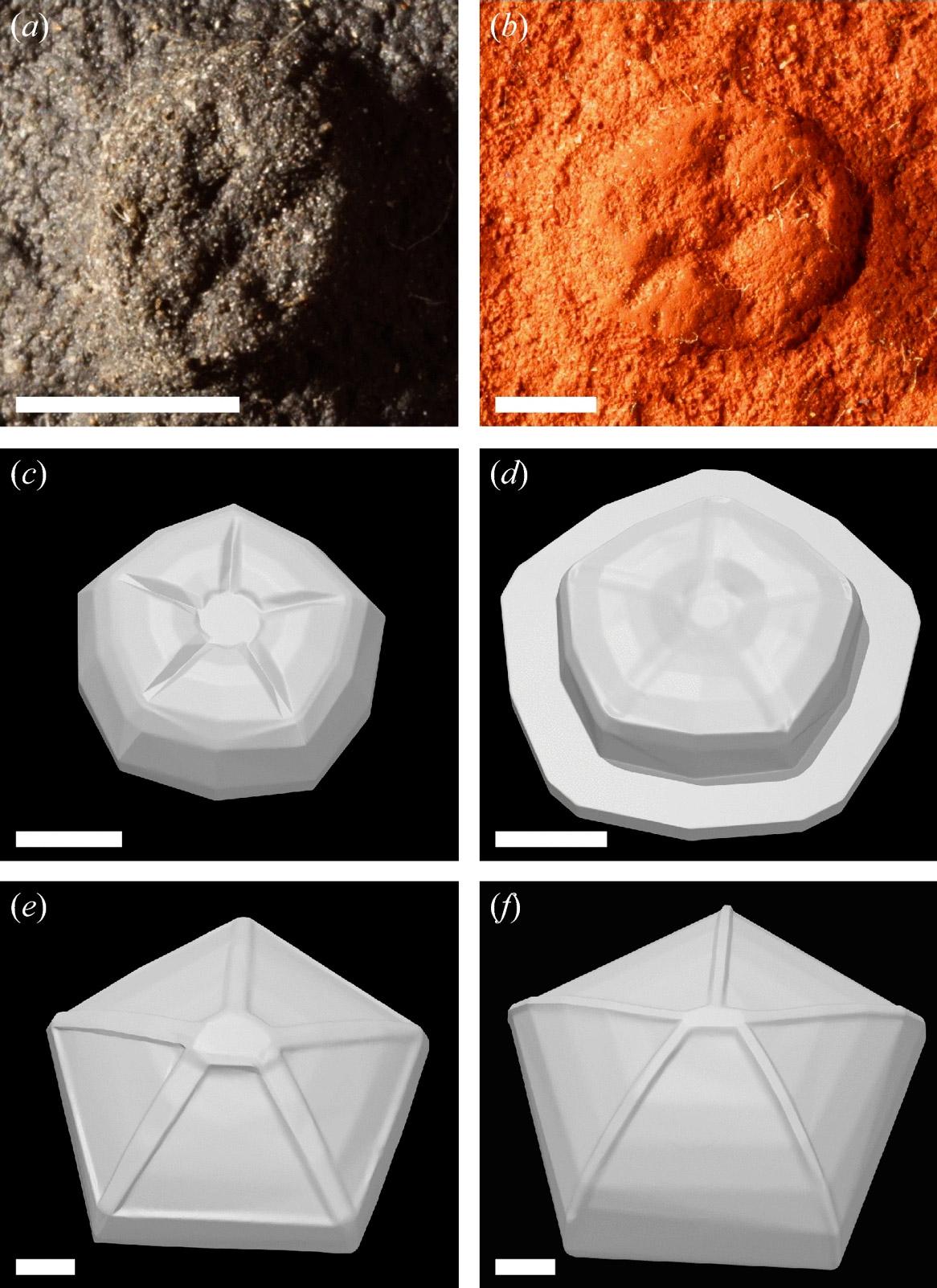

Top - Fossil moulds of Arkarua adami from Devil's Peak and Chace Range, Flinders Ranges; Middle - 3D models of small and large Arkarua from the Flinders Ranges; Bottom - Cambrian echinoderm models used for comparison in the study. Scale bars = 2 mm. View larger image

The multi-celled organisms of the Ediacara Biota are the oldest complex life forms on our planet. In most cases they are very different from anything around today, or for that matter, around for the last 500 million years of animal evolution, making it difficult to put them in the appropriate branch of the tree of life.

“Similarly, their bizarre shapes do not easily lend themselves to comparison with the modes of life of modern marine organisms, but in this study, researchers used three-dimensional modelling and computational fluid dynamics to establish the feeding mode of Arkarua," says Associate Professor García-Bellido.

"The modelling measured the water flow over the body of Arkarua, compared with the slightly younger, Cambrian seafloor dwelling echinoderms (cousins of living sea urchins and sea stars).”

Their analyses published in Nature’s Scientific Reports found that Arkarua was capable of affecting the flow patterns over the seafloor in a way that would allow organic particles to be directed towards the central depression and the associated grooves on its dorsal surface, supporting its interpretation as a passive suspension feeder.

This strategy has been reported in a variety of modern invertebrates fixed to the seafloor, like bivalves, corals and crinoids.

Computational fluid dynamics surface plots (horizontal and vertical cross-sections) at four different speeds over the small and large Arkarua models (top) and the 2 echinoderms (bottom). Arrows indicate direction of water flow and colours indicate speed. View larger image

Suspension feeding is an important ecological strategy in our oceans today, as it provides a transfer of energy from organisms swimming in the water column to those living on the seafloor. Establishing when suspension feeding first evolved has crucial implications in researchers understanding of the origins of the complex, modern biosphere in general, and marine food webs in particular.

Applying this type of modelling and computational fluid dynamics to other Ediacaran organisms, the researchers expect to reveal insights into the enigmatic multicellular organisms that first populated our planet.

This new technique and further fossil discoveries in the Flinders Ranges will help visitors to the soon-to-be declared Ediacara-Nilpena National Park envision the diversity of forms and complexity of lifestyles thriving over half a billion years ago.

These items are on display and can be visited at the South Australian Museum’s Ediacara Gallery.

Sciences research in focus

- Pentaradial eukaryote suggests expansion of suspension feeding in White Sea-aged Ediacaran communities, Nature Scientific Reports