New research shows zoonotic virus prevalence in Adelaide's Grey-headed flying foxes

For the first time, University of Adelaide scientists have uncovered what zoonotic viruses the city's Grey-headed flying fox population has been exposed to.

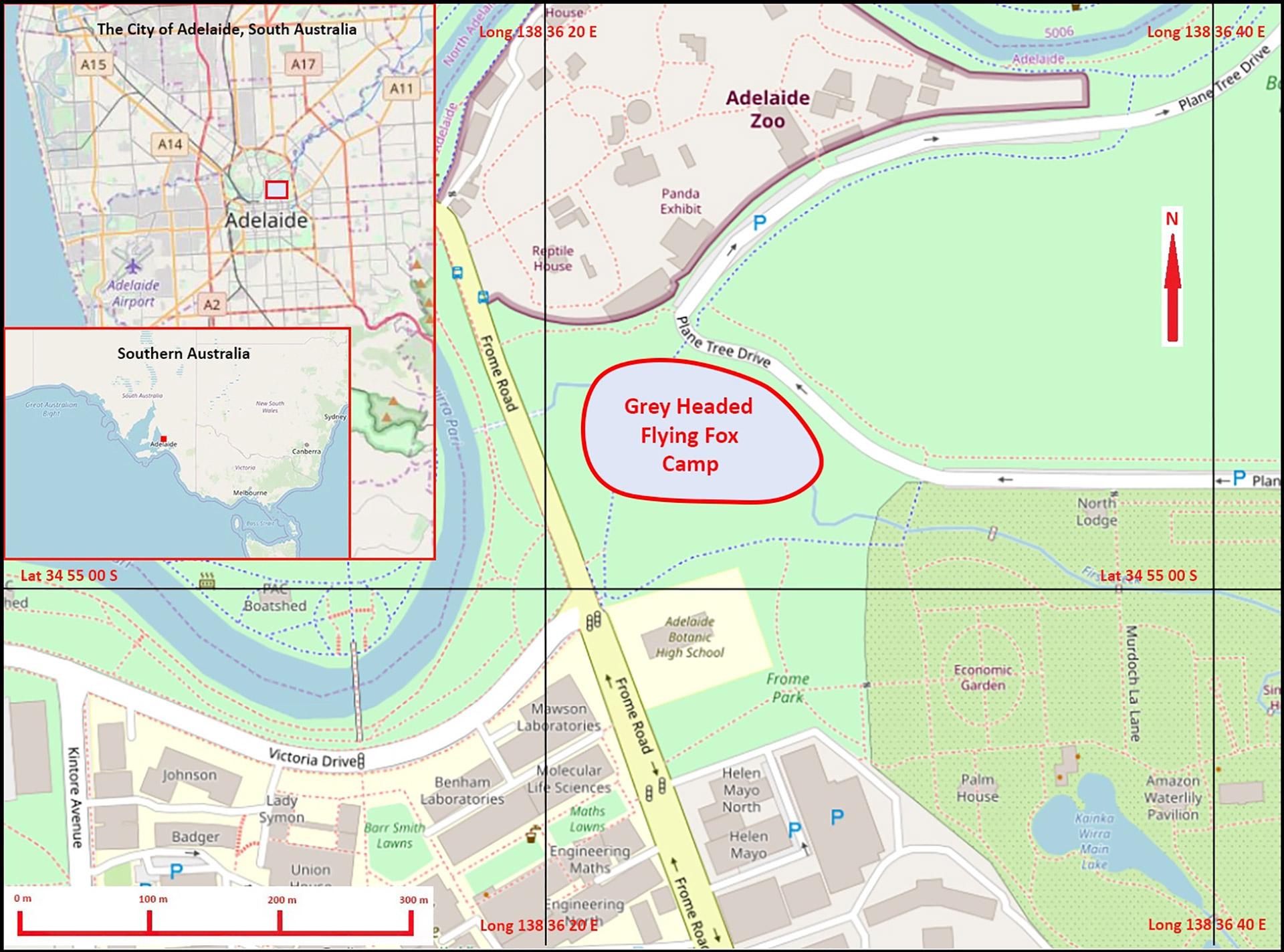

Australia's largest bat, the Grey-headed flying fox (Pteropus poliocephalus) moved to South Australia in 2010 and set up camp in the Adelaide Park Lands - interestingly, 200 metres from the University's North Terrace campus.

Research by scientists in the School of Animal and Veterinary Sciences learned that the population has been exposed to a number of zoonotic viruses - including Hendra virus that can be transmitted to humans via horses. But they have not found evidence of exposure to Australian bat lyssavirus.

The research, published in PLOS ONE, details three years of research into the local flying fox population and their exposure to paramyxoviruses (Hendra, Cedar and Tioman) and a rhabdovirus (Australian bat lyssavirus).

What is a zoonotic virus?

Hendra virus and Australian bat lyssavirus are classified as zoonotic viruses - meaning they can be transmitted from animals to humans.

- Hendra virus can be transmitted to horses and then to humans by airborne droplets causing acute respiratory diseases and death.

- The risks posed by Hendra virus are extremely low with only seven cases in humans, all of whom had been in contact with infected horses, never directly from bats.

- In the case of Australian bat lyssavirus, humans and other animals need to be bitten or scratched by a carrier. Infection in humans can cause serious illness.

“It’s positive to discover that the risk of lyssavirus transmission in South Australia is lower than anticipated."Dr Wayne Boardman, Senior Lecturer, School of Animal and Veterinary Sciences, The University of Adelaide

Lead author Dr Wayne Boardman says given the Grey-headed flying foxes are known carriers of viruses, it was important to understand what the local population of flying foxes had been exposed to.

“Grey-headed flying foxes are essential ecosystem service providers contributing to large-scale pollination and seed dispersal and are a nationally threatened species,” Dr Boardman said.

“They have this extraordinary ability to be infected with viruses but don’t show any ill effects, except for one virus; the Australian bat lyssavirus. It’s important to understand what risks these animals pose to humans.

“We have found the local population has developed antibodies for the Hendra, Cedar and Tioman viruses, meaning they have been exposed at some stage in their lives.

“What’s good news for South Australia is that the local population has not shown exposure to Australian bat lyssavirus, which in humans causes serious illness including paralysis, delirium, convulsions and death.

“It’s positive to discover that the risk of lyssavirus transmission in South Australia is lower than anticipated.

“However, this doesn’t mean that flying foxes are safe to touch; only people with experience in handling these animals should ever come into contact with them.”

Moving in search of a suitable climate and food

Location of the Grey-headed flying fox camp in Adelaide’s Botanic Park and relationship to central Adelaide and Southern Australia. Larger version

The Grey-headed flying fox has made the Botanic Gardens in Adelaide home for the past 10 years, having come to South Australia from New South Wales and Victoria in search of a suitable climate and food.

The research on the local population has also revealed that Hendra virus levels were significantly higher in pregnant females; results that align with findings interstate. However, good body condition is a risk factor for a bigger proportion of the population being exposed to Hendra virus because the flying foxes are in better condition in winter than summer, which is the opposite of what has been found in the eastern states.

Dr Boardman said this means the flying foxes are finding plenty to eat here in winter time specifically, enjoying the introduced foods that are planted in gardens, along roads and in parklands, similar to the normal food source for those in the eastern states.

“The Grey-headed flying fox is certainly enjoying the local environment during the South Australian winter, but we have seen on numerous occasions that the heat in summer certainly knocks the population around so we are looking at ideas to help support them during heatwaves in summer using high level misters and sprinklers.”

The research was carried out in partnership with CSIRO’s Animal Health Laboratory in Geelong, South Australian Museum and Zoos South Australia.

Further reading

Main image credit: Craig Greer