Study sheds new light on vein formation in plants

An international team of researchers including scientists from the University of Adelaide, has found plant hormones known as strigolactones suppress the transportation of auxin, the main plant hormone involved in vein formation, so that vein formation occurs slower and with greater focus.

The research, published in Nature Communications, brings new knowledge about how hormones regulate plant growth, knowledge that will ultimately contribute to scientists’ quest to improve crop productivity.

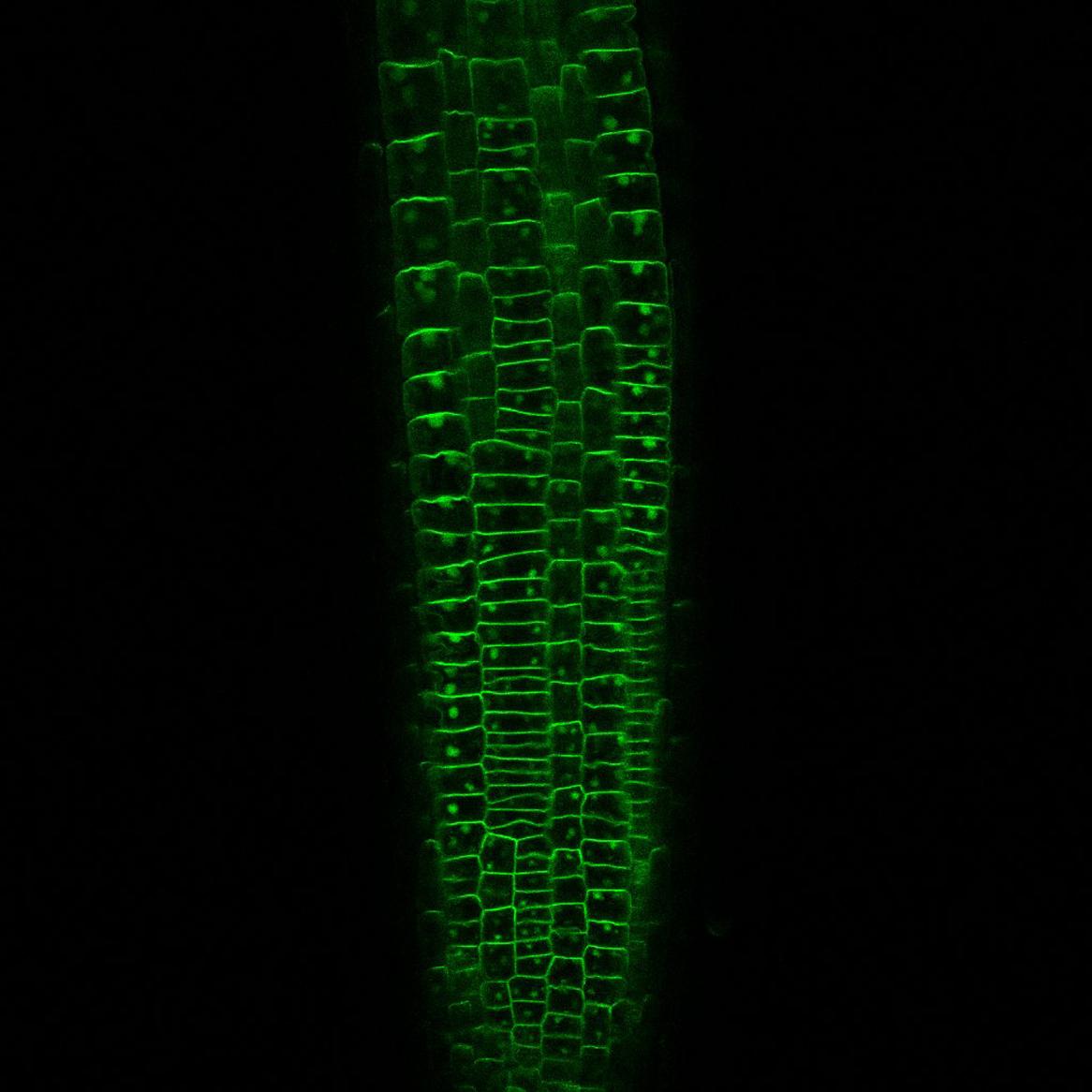

PIN2 auxin transport protein that is internalised (green dots) by strigolactone treatment to epidermal root cells of Arabidopsis thaliana.

Image by Philip Brewer.

Co-author, Dr Philip Brewer of the University of Adelaide’s Waite Research Institute, said scientists know that the interaction between strigolactones and auxin is important for plant responses, but further research in this area is essential to learn how.

Vascular plants have veins in leaves, stems and roots that carry water and nutrients to cells, and provide structural support. The hormone auxin flows from new leaves and buds to connect them together and joins them with the stem, and re-joins veins at wound sites, a process call canalisation.

“Although only recently identified, what we know about strigolactone hormones is that they help plants respond to environmental conditions, such as optimising plant growth to match soil nutrient levels,” said Dr Brewer.

“By observing the interaction of the two hormones in pea and thale cress plants in this study, we found that when applied, strigolactones reduce the transport of auxin and slow vein formation.

Dr Philip Brewer

“Strigolactones also supress auxin as it flows through root tips. Specifically, strigolactones limit the way auxin promotes its own transport out of cells,” said Dr Brewer.

Dr Brewer said plant hormones like auxin and strigolactones have great potential to improve crop productivity.

“However, understanding how they act is still a major research challenge, and applying hormones in agriculture often results in unwanted side effects,” said Dr Brewer.

“Improved knowledge of how the hormones act allows us to uncover ways to fine-tune hormone responses so that we can realise the benefits and limit the side effects.

“While more research is needed in this field, this study contributes to fundamental knowledge of plant biology and offers hope of finding new ways to adapt crops to increasingly difficult climate conditions,” Dr Brewer said.

The international collaboration also included researchers from Institute of Science and Technology, Austria; China Agricultural University, Beijing; University of Silesia, Poland; Masaryk University, Czech Republic; Mendel University, Czech Republic; Palacký University, Czech Republic; and the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna.