The Federated States of Degradia

‘A nation humanity must take responsibility for’, writes Professor Andy Lowe.

Andy Lowe

Professor of Plant Conservation Biology

With almost a third of arable land classified as degraded, what can we do to reverse the rapid pace of degradation and can we do it in a way that benefits us?

For most of our history we have been hunters and gatherers – low in numbers, with rudimentary technology and very limited impact on our environment.

Forests were largely intact; water was clean, and the air was pure. If we had the chance to go back in time and observe our planet from space it would be virtually impossible to even notice our presence on the globe.

However, things have recently taken a very different turn. Countless breakthroughs in technology, medicine and agricultural practices have radically changed the influence that we, as a species, are having on our planet.

In only a few thousand years our population has exploded and so has our impact.

Carbon Neutral, a Perth-based carbon offset provider, has planted 30 million native trees and shrubs since 2008. Their ambition is to plant a 200km highway of trees across Western Australia’s Wheatbelt, as shown in this image taken using a carbon neutral drone by photographer Russell Ord.

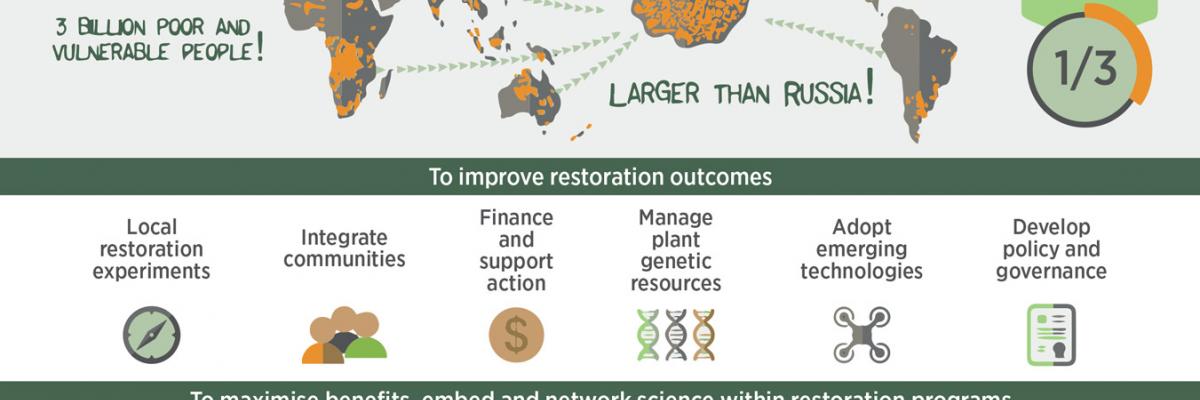

Today, when observing our planet from space, a very different picture appears. Enormous areas that used to be covered by uninterrupted forests are now occupied by farms, pastures and megacities. Much of the earth is now overexploited and degraded by unsustainable management. In fact, approximately a third of the world’s ecosystems are now, in some way, degraded.

To put this in perspective, if we were to combine the most degraded areas into one geopolitical boundary, it would form a country larger than Russia. This country, which we could call the ‘Federated States of Degradia’, would be inhabited by 3 billion of the world’s poorest and most vulnerable people.

So, what should we do about Degradia? Can we halt its ever-expanding borders?

Should we let it become almost uninhabitable for human beings? Why are we even thinking of terraforming Mars when our priorities should be here?

Planting trees is a tried and tested way of restoring degraded lands and the good news is that there are now ambitious restoration agreements in place.

The Bonn Challenge, for example, has set a global goal of restoring 350 million hectares by 2030. Whilst impressive, these goals will still only address a fraction of the world’s degraded areas and a lot more work remains to be done. benefits, embed and network science within restoration programs

Let’s be honest, restoring the planet to the ‘Garden of Eden’ it was thousands of years ago simply isn’t an option – the reality is billions of people are sharing this earth. We need pragmatic innovation to restore Degradia.

As individuals we can all help by participating in tree planting schemes and ticking that box to offset carbon emissions from our international air travel.

However, if we focus on monoculture plantings for carbon benefits, this misses opportunities to restore a broader spectrum of biodiversity and fails to harness a wider range of nature’s benefits, known as ecosystem services.

Science now allows us to engineer our landscapes through plantings that provide ecosystem services to purify air and water, rebuild soil fertility, pollinate crops, control soil erosion, sequester carbon and even improve human health.

Investing in evidence-based restoration approaches allows us to terraform degraded landscapes… here on this planet. Such investment has clear economic and social returns, above and beyond the initial outlay.

Imagine mitigating climate change, saving our threatened species and improving the health of communities all at the same time. Terraforming ecosystems is a smart way of realising multiple benefits for people, businesses and the planet. We need to be bold enough to pull the inhabitants of Degradia out of environmental poverty.

So, what next?

At the University of Adelaide’s Faculty of Sciences, my team works with businesses to design plantings that realise multiple benefits for urban developments and rural communities. Right now, we are working with apple and pear growers in the Mt Lofty Ranges and lucerne seed growers in south-east South Australia, where we are helping them to plant biodiverse hedge rows and keep paddock trees for the pollination benefits they provide.

Planting shelter belts to fix carbon also helps protect young livestock from wind chill and dramatically increases survivorship. These types of triple bottom line outcomes are good examples of the growing movement of regenerative agriculture, where farmers are repairing the land and generating sustainable incomes.

As gardeners, you can do your bit too. We can link you up with community projects or provide information for you to terraform your own backyard and help create greener suburbs and cities.

But whatever you do, join us in helping to restore Degradia.

Sciences research in focus

This article appears in the The Diggers Club's winter 2021 magazine and has been republished here with permission.

The concept of the Federated States of Degradia was co-created by Andrew Lowe, Dr Nick Gellie, Martin Breed, Corri Baker and Tulio Rossi and is based on the publication: Gellie NJC, Breed MF, Mortimer PE, Harrison RD, Xu J, Lowe AJ (2018) Networked and embedded scientific experiments will improve restoration outcomes. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 16:288-294.

The concept for the text, infographic and video cartoon were created by Andrew Lowe, Nick Gellie, Martin Breed, Corri Baker and Tulio Rossi, and were produced by Animate Your Science and supported by the Environment Institute, University of Adelaide.