Kangaroo Island bee B&Bs aim to save native pollinators

Images: Remko Leijs

Native bees severely impacted by Kangaroo Island bushfires this year are being built new homes in a collaborative project involving the local community and scientists from the University of Adelaide and SA Museum.

The green carpenter bee (Xylocopa aerata) has been extinct on mainland South Australia for more than a century – and scientists worry that last summer’s catastrophic bushfires have significantly increased the extinction risk of the Kangaroo Island population.

To help save the species, new nesting stalks are being built for these bees, through help of the Kingscote Men’s Shed and funds raised via the Australian Entomological Society and the Wheen Bee Foundation.

“After the 2007 fires, we bolstered the remaining population by providing nesting materials until new dead Banksia trunks, suitable for nesting, would become available,” says entomologist Dr Katja Hogendoorn from the University of Adelaide’s School of Agriculture, Food and Wine.

“In long-unburnt areas adjacent to Flinders Chase National Park, carpenter bee nests were still present. From there, they colonised the many dry grass tree stalks that resulted from the fire in the park.”

But the grass tree stalks only remain available for a period of 3-5 years after fire, so after that, scientists placed new artificial nesting stalks in fire-affected areas where the bees still occurred. Almost 300 female carpenter bees have successfully used the stalks to raise their offspring.

“To see our efforts - and most importantly, more than 60 years of unburnt Banksia habitat that these bees rely on - destroyed by the 2020 fire was utterly devastating,” says Dr Hogendoorn.

“There were more than 150 nests containing mature brood in the stalks we had provided.”

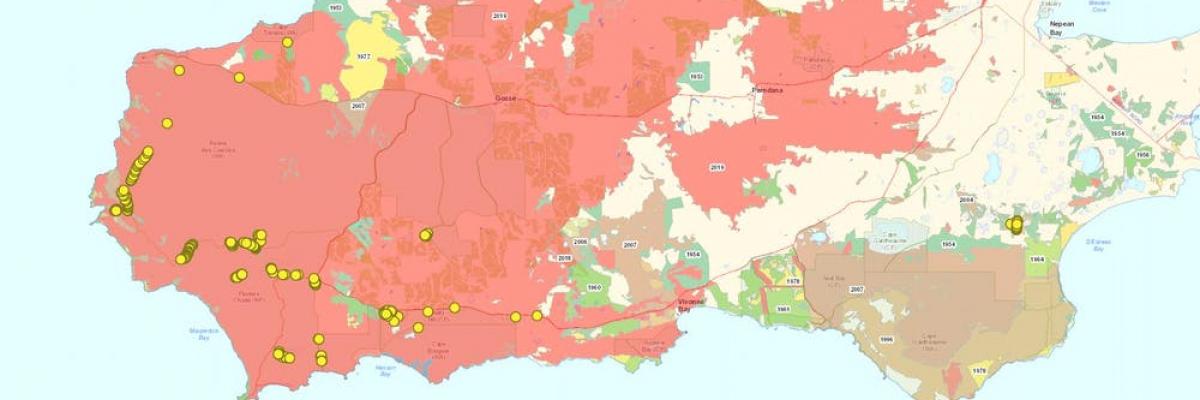

The yellow dots represent known green carpenter bee nests. In red: the area burnt in 2020. Only a subset of the remaining green and yellow patches still have the right vegetation for the green carpenter bee. Image: Nature Maps SA/Remko Leijs

Scientists will survey remnant long unburnt areas on Kangaroo Island for remaining green carpenter bees. They will also search conservation areas around Sydney, and in the Great Dividing Range in New South Wales, where much of the species’ natural range was also burnt.

“Encouragingly, we have already found a few natural nests on Kangaroo Island, but the remaining suitable areas are small and isolated, and densities are likely to be low,” says Dr Hogendoorn.

Dr Hogendoorn and colleagues at SA Museum are working with Kangaroo Island landholders to place new nesting stalks in areas with good floral support, to enhance reproduction and help the bees disperse into conservation areas once suitable.

“As we have learnt, success is not guaranteed… extensive and repeated bush fires, combined with asset protection and fuel reduction burns, are making longtime unburnt habitat increasingly rare,” says Dr Hogendoorn.

What’s the buzz with green carpenter bees?

Image: A male green carpenter bee / Remko Leijs

- The green carpenter bee is a buzz-pollinating species. Buzz pollinators are specialist bees that vibrate the pollen out of the flowers of buzz-pollinated plants.

- Many native plants, such as guinea flowers, velvet bushes, Senna, fringe, chocolate and flax lilies, rely completely on buzz-pollinating bees for seed production. Introduced honey bees do not pollinate these plants.

- Carpenter bees are so named because they excavate their own nests in wood, as opposed to using existing holes.

- With a body length of about 2 centimetres, it is the largest native bee in southern Australia.

Vulnerable to fire

Green carpenter bees are vulnerable to fire and the availability of their nesting materials is intricately connected with fire.

- The bees mainly dig their nests in two types of soft wood: dry flowering stalks of grass trees and, crucially important, large dead Banksia trunks. Unfortunately, dead wood burns easily.

- Grass trees flower prolifically after fire, but the dry stalks are only abundant between two and five years after fire.

- Banksia species don’t survive fire, and need to grow for at least 30 years to become large enough for the bees to use. With increasingly frequent and intense fires, there’s not enough time for Banksia trunks to grow big enough, before they’re wiped out by the next fire.

- If the nest burns before the offspring matures in late summer, the adult female might fly away but won’t live long enough to reproduce again.

- The bees need floral resources throughout the year to survive.

The carpenter bee is not the only species under threat from wildfire. Many Australian plants and animals are not resilient to high frequency fires, no matter their intensity or time of year.

As for Kangaroo Island, there’s also concern for several small mammals, glossy black cockatoos, and a range of invertebrate species.

Further reading

Check out The Conversation article titled, ‘‘Jewel of nature’: scientists fight to save a glittering green bee after the summer fires’ by University of Adelaide scientists Dr Katja Hogendoorn, Dr Remko Leijs (also South Australian Museum) and Dr Richard Glatz. Parts of the original article have been published here.